Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > STRESS > Volume 28(3); 2020 > Article

-

Original Article

-

최희승

, 김수미

, 김수미 , 고희성

, 고희성

- Parents’ Perceptions and Responses to Parent-adolescent Conflict Situations: A Mixed Methods Approach

-

Heeseung Choi

, Sumi Kim

, Sumi Kim , Heesung Ko

, Heesung Ko

-

stress 2020;28(3):142-152.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17547/kjsr.2020.28.3.142

Published online: September 30, 2020

1 서울대학교 간호대학, 간호과학연구소

2 서울대학교 간호대학

3 예수대학교 간호학부

1College of Nursing and the Research Institute of Nursing Science, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

2College of Nursing, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

3Department of Nursing, Jesus University, Jeonju, Korea

- Corresponding author Heesung Ko Department of Nursing, Jesus University, 383 Seowon-ro, Wansan-gu, Jeonju 54989, Korea Tel: +82-63-231-7786 Fax: +82-63-230-7790 E-mail: hsko@jesus.ac.kr

Copyright © 2020 by stress. All rights reserved.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,515 Views

- 28 Download

Key messages

-

Background

- Understanding how parents cognitively and emotionally perceive and respond to parent-child conflicts would provide a basis for targeted and effective parent education programs. The specific aims of this online mixed methods research study were to (1) categorize parents of adolescents based on their level of parental self-efficacy, parent-child communication, parent-child relationships, parent-child conflicts, and parental stress; and (2) explore parent-child conflict situations and parents’ perceptions and responses to them in each group.

-

Methods

- A total of 103 parents with adolescent children aged 11∼16 years were recruited from five cities in Korea to participate in the study. Participants completed an online questionnaire about parent-child relationships and described a parent-child conflict situation that occurred within the past week and their perceptions and responses to it. We used cluster and content analyses for quantitative and qualitative data, respectively.

-

Results

- The study revealed two clusters: adequate parent-child relationship (group 1) and inadequate parent-child relationship (group 2). The key variable distinguishing the two groups was parental self-efficacy. Although parents in both groups generally experienced frustration, anger, worry, discouragement, and disappointment in the conflict situations, the two groups differed in their perceptions and responses to these situations.

-

Conclusions

- Results suggested that parent education programs should focus on improving parental self-efficacy. Additionally, the programs should provide an opportunity for parents to practice self-reflection, help them understand the link between emotion-thought-behavior based on cognitive model, and thus, effectively manage parent-child conflict situations.

Abstract

- 본 연구는 부모-자녀 관계와 관련된 양적 변수에 따라 구분된 각 그룹들에서 부모자녀 갈등의 주제, 갈등상황에서 부모의 인식과 반응의 질적인 차이를 확인하고자 시도되었다. 국내 5개 도시에서 청소년 자녀를 둔 부모 103명이 부모효능감, 부모-자녀 의사소통, 부모-자녀 관계, 부모-자녀 갈등, 부모스트레스 관련 온라인 설문에 참여하였고, 이들은 청소년 자녀와의 갈등상황을 직접 기술하였다. 5개 변수의 군집분석결과 두 개의 그룹으로 분류되었고 두 그룹의 부모들은 모두 청소년 자녀와 갈등상황에서 실망, 분노, 걱정, 좌절 등의 감정을 경험하였으나 갈등을 인식하고 반응하는 양상에서는 차이가 있었다. 본 연구결과는 향후 부모자녀 관계를 향상시키기 위한 부모교육프로그램 구성의 기초자료가 될 것이다.

- Parent-child relationships, which are often eva-luated by the quality of parent-child communi-cation, conflict, and satisfaction, have been known to be a significant predictor of adolescent mental health (Quach et al., 2015). Parent-child communication is a direct and indirect risk factor in the mediation of adolescents’ depression and suicidal ideation (Shin et al., 2014). Furthermore, parent- child conflict was significantly correlated with adolescents’ problematic behaviors (Jang et al., 2014), and influences from the parent-child relationship continued throughout the adolescents’ growth (Klahr et al., 2011). According to a 30-year obser-vation of adolescents, 5∼24% had unsatisfactory relationships with their parents, and these adoles-cents were 20∼80% more likely to experience mental health problems in their 40s than those who had satisfactory relationships with their parents (Morgan et al., 2012). Furthermore, an insecure parent-child attachment was found to be signifi-cantly associated with a child’s drug abuse in both a longitudinal quantitative study (Brook et al., 2009) and a qualitative study (McLaughlin et al., 2016).

- The quality of the parent-child relationship is also closely associated with a child’s academic performance (Yuan et al., 2016). Particularly, the quality of the parent-child relationship not only directly but also indirectly improves theacademic performance of Asian college students by incre-asing academic efficacy, in contrast to their European counterparts. In other words, the parent child relationship influences various aspects of health and development in Asian adolescents.

- To improve the quality of the parent-child re-lationship, the importance of developing parent education programs aimed at improving parental self-efficacy hasbeen emphasized, and such programs have been provided. Improving self-efficacy was found to help parents build confi-dence in playing a parental role, lower parental stress during the child-rearing process, and help parents effectively deal with conflict situations with their children (Amin et al., 2018).

- Compared to universal prevention programs that target all parents, selective or indicated prevention programs designed to address the specific needs of high-risk groups are necessary and would be more cost-effective (O’Connell et al., 2009). To develop targeted and effective parent education programs, the context within which parent-child relationships occur as well as the levels and associations among the various aspects of the parent-child relationship need to be illuminated. Fuligni (2016) learned that quan-titative analysis alone was not sufficient enough to understand the nature of parent-adolescent rela-tionship in Asian American families. Integrating a qualitative approach enabled him to understand the dynamics of parent-child relationships and gain key insights of this relationship in the specific cultural context.

- Mixed methods research has been widely used to explore diverse social and behavioral issues since this approach was introduced about 30 years ago (Blake, 1989). The mixed methods approach provides a more complete understanding of the phenomenon by comparing and integrating both quantitative and qualitative datarather than just applying a single approach (Creswell et al., 2017). To explore the impact of parenting on a child’s adjustment and the level of coherence between quantitative and qualitative findings, Bombi and colleagues (2015) conducted a mixed method re-search and claimed that the integration of a cluster analysis of parenting practices and the analysis of individual interviews about parenting styles deepened their understanding of the rela-tionship between the parent-child relationship and the child’s ad-justment.

- For Korean families, a quantitative exploration of the effect of parent-child conflictsand conflict resolution on behavioral problems among adoles-cents has been performed (Jang et al., 2014). Furthermore, mothers’ experiences of overcoming conflicts with their adolescent child (Lee and Han, 2013) and parents’ and children’s perceptions about their transition to adolescence have been explored using a qualitative approach (Soh et al., 2014). Until now, very few studies have explored the quality of parent-child relationships and the context of parent-child conflicts using the mixed methods approach in Korea. Thus, we conducted the present study to enhance the understanding ofparent-child relationships by comparing and integrating quantitatively measured parent-child relationships with the context of parent-child conflicts revealed from qualitative data. The specific aims of the study were to: 1) categorize parents of adolescents into groups based on their levels of parental self-efficacy, parent-child com-munication, satisfaction with parent-child rela-tionships, parent-child conflicts, and parental stress and 2) explore parent-child conflict situations and parents’ perceptions and responses to the conflict situations in each group. Gaining a comprehensive understanding of how parents cognitively and emotionally perceive and respond to parent- child conflicts would provide a basisfor targeted and effective parent education programs.

Introduction

- 1. A brief description of the larger study and study procedure

- This online study used a convergent mixed methods design (Creswell et al., 2017). The sample for the present study was drawn from a larger study which was designed to test the efficacy of a newly developed 4-week online parent education program for Korean parents of adolescents, "Stepping Stone." Descriptions of the larger study are discussed elsewhere (Choi et al., 2016). The Stepping Stoneprogram was designed to improve parental knowledge, parental self-efficacy, parent child communication, and parent-child relation-ships, and to reduce parental stress and parent- conflicts. Parentsof adolescents who were capable of understanding Korean and currently living with their children were eligible to participate in the study.

- After obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board of the S. University and the principals of the target schools, participants were recruited from schools through school newsletters that were sent to students’ families. Additionally, parents who received information about the purpose and procedure of the study from their local commu-nities and wished to participate were told to directly contact the investigator. The investigator gave the potential participants the address and ID for the study website and explained the procedure. Parents who agreed to participatein the Stepping Stone program were required to complete one education session per week for four weeks and weekly assignments between the sessions. For example, parents watched a 23-minute video introducing a method for analyzing parent-child conflicts that was based on a cognitive model. Afterwards, as an assignment for the session, parents were asked to describe situations that induced conflict between themselves and their children within the past week, and describe their emotions, thoughts, behaviors, and consequences of those behaviors at the time. It took about 20 minutes for the parents to complete the assignment. The partici-pants received a ₩10,000 or 20,000 gift certificate for their participation depending on the number of sessions they completed.

- 2. Sample size

- The sample size for the original study was determined based on the estimated design effect calculated from our pilot study. Assuming an attrition rate of 15%, power analysis for repeated measures analysis of variance design indicated that at least 54 participants per group were required to detect a medium effect size (d=0.5) with 80% power (a=.05, two-tailed). The sample for the present study consists of 103 parents of adolescent children aged 11∼16 years who com-pleted the baseline survey and the assignments given in the Stepping Stone program. For the present study, we analyzed the survey data assessing parental self-efficacy, parent-child communication, parent-child relationship, parent-child conflict, and parental stress as well as the qualitative data obtained from the assignment that the parents completed using a convergent mixed methods design.

- 3. Measurements

- Quantitative data was collected from participants using the following five scales. Parental self-efficacy was measured using the Parental Self-Efficacy Scale (PSS) originally developed by Caprara et al.(2004) and modified and adapted for Korean parents by Choi et al.(2012). The scale consists of items that measure the ability to recognize and respond to problems related to mental health, such as a child’s peer relations, depression, and suicidal ideation. The scale consists of 16 items on a 7-point Likert scale. The total score ranges from 16 to 112, with higher scores representing better parental self- efficacy. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (a) for the PSS exhibited excellent reliability (a=.93) in both a previous study (Choi et al., 2012) and the present study (a=.91).

- The Parent-Child Communication Scale was developed based on the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Harris et al., 2005) and the Parent Adolescent Communication Scale (Barnes et al., 1985), and was modified by Choi et al.(2012). This scale comprises items concerning openness and problems of communication. This 10-item scale is rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 4 (agree). The total score ranges from 10 to 40, with a higher score indicating a higher level of parent-child com-munication. This tool was found to have acceptable reliability in the previous study (a=.81) and in our study (a=.85).

- Parent-Child relationship was measured with the scale developed by the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Carolina Population Center, 2006) and modified by Choi et al.(2012). This tool consists of two items about parent-child communication that are rated on a 5-point Likert scale and one item about parent-child intimacy rated on a 10-point Likert scale. The total score ranges from 3 to 20, with a higher score indicating higher satisfaction with the parent-child relationship. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.82 in this study.

- The Conflict Behavior Questionnaire-Parents is a widely used instrument for measuring parents’ perceived parent-child conflicts and has been assessed as capable of screening for healthy parent-child groups, as well as parent-child groups which encountered severe stress and clinical problems (Robin and Foster, 2002). The tool comprises 20 items, and each item is answered with either true or false. The total score ranges from 20 to 40, with a higher score indicating a high level of parent-child conflicts. This scalehad acceptable reliability in the previous studies (a=.89∼.92) (Choi et al., 2012; Choi et al., 2016), and in this study (a=.88).

- The original Parental Stress Scale is a 51-item scale developed by Sung (2013) to measure thestress experienced by parents while rearing adolescent children. For this study, 35 items from the "parent section" and "parent-child section" were used. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale. The total score ranges from 35 to 140, with a higher score indicating a higher level of parental stress. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.93 at development and 0.89 in the present study.

- Five open-ended questions developed based on the cognitive model were used for an in-depth qualitative exploration of how parents perceive andrespond to parent-child conflicts both cogni-tively and emotionally. Parents were told to write their responses to five questions: (1) What hap-pened?, (2) How did you feel?, (3) What was the first thought that occurred to you?, (4) What were your reactions or behaviors?, and (5) What were the consequences?

- 4. Analysis

- A preliminary analysis of quantitative data enabled us to identify evidence on differences in the response patterns in the assignment depending on the parent-child relationship scores. Thus, we categorized parents of adolescents into two groups based on the composite of parental self- efficacy level, parental stress, parent-child communication, parent-child conflicts, and parent-child relationships. Next, we explored the differences in context using a qualitative approach by examining and comparingparents’ perceptions and conflict management strategies utilized in parent-child conflicts between the two groups. A detailed procedure of data analysis is described below.

- Parents’ perceived relationships with their children were analyzed usingcluster analysis based on five variables: parental self-efficacy, parent-child communication, parent-child relationship, parent child conflicts, and parental stress. Cluster analysis is useful in clustering a sample into groups with similar characteristics and enables the identi-fication of the characteristics of each group. The data analysis process was conducted as follows. First, a correlation analysis was performed to examine the characteristics that could potentially be clustered. Second, principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical cluster analysis were per-formed to estimate the appropriate number of clusters. Based on this number, a nonhierarchical cluster analysis technique,known as K-means analysis, was performed. The differences among clusters were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. Furthermore, participants’ demographic information and frequency of parent-child conflicts were analyzed using descriptive statistics. All quantitative data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 and SPSS 23.

- We used content analysis to analyze qualitative data (Hsieh et al., 2005). Two researchers inde-pendently read through the qualitative data multiple times to identify codes, categories, and themes. First, parent-child conflicts were categorized based on the topics. Conflicts experienced by each parent were classified into these categories, and the frequency of conflicts was computed. We analyzed the characteristics of each cluster by focusing on the characteristics of parent-child conflicts and parents’perceptions and responses to the conflict situations. Finally, we compared and integrated findings from the quantitative and qualitative data.

Methods

1) Quantitative data

2) Qualitative data

1) Quantitative data

2) Qualitative data

- 1. Cluster analysis results and general characteristics of each group

- A total of 103 parents recruited from five cities participated in this study (56 parents from schools and 47 parents from local communities). There were no significant differences in the demographic characteristicsand study variables between the participants recruited from schools and those recruited from local communities. The correlations among scores from the five scales were analyzed in order to identify the type of parent-child relationship reported by the parents. Parental self-efficacy was positively correlated with parent-child communication (r=.61, p<.01), while it (r=.67, p<.01) was negatively correlated with parent-child conflict (r=−.48, p<.01) and parental stress (r=−.55, p<.01). Furthermore, parentchild communication was positively correlated with parent-child relationship (r=.70, p<.01), but negatively correlated with conflict (r=−.48, p<.01) and parental stress (r=−.62, p<.01). Parent-child relationship was negatively correlated with parent- child conflict (r=−.74, p<.01) and parental stress (r=−.70, p<.01), whileparent-child conflict was positively correlated with parental stress (r=.60, p<.01) (Table 1).

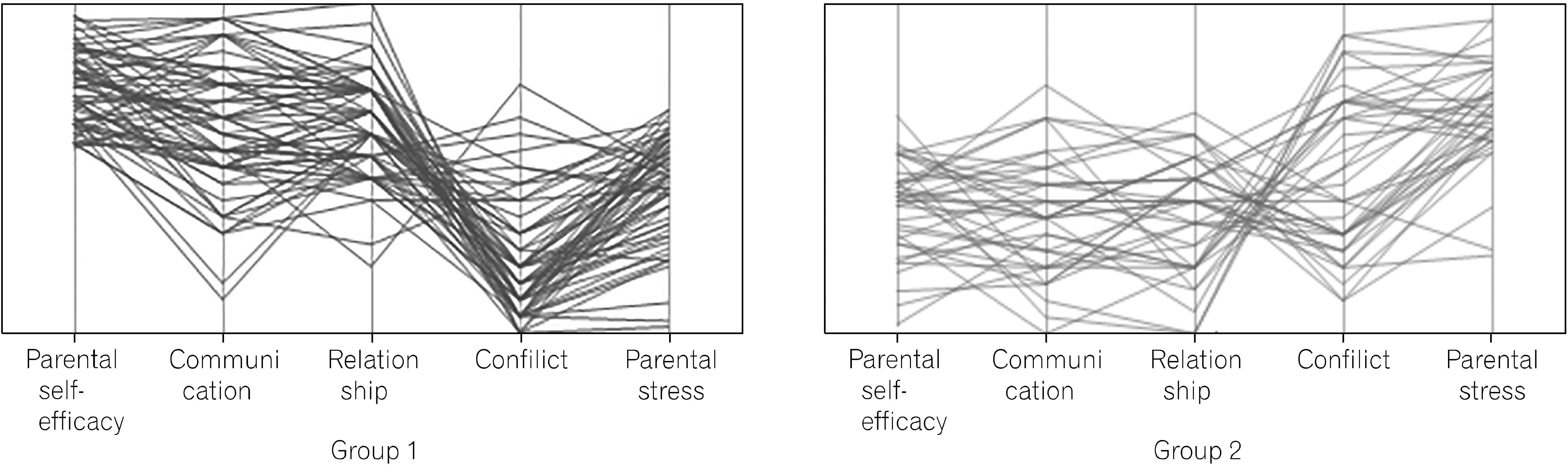

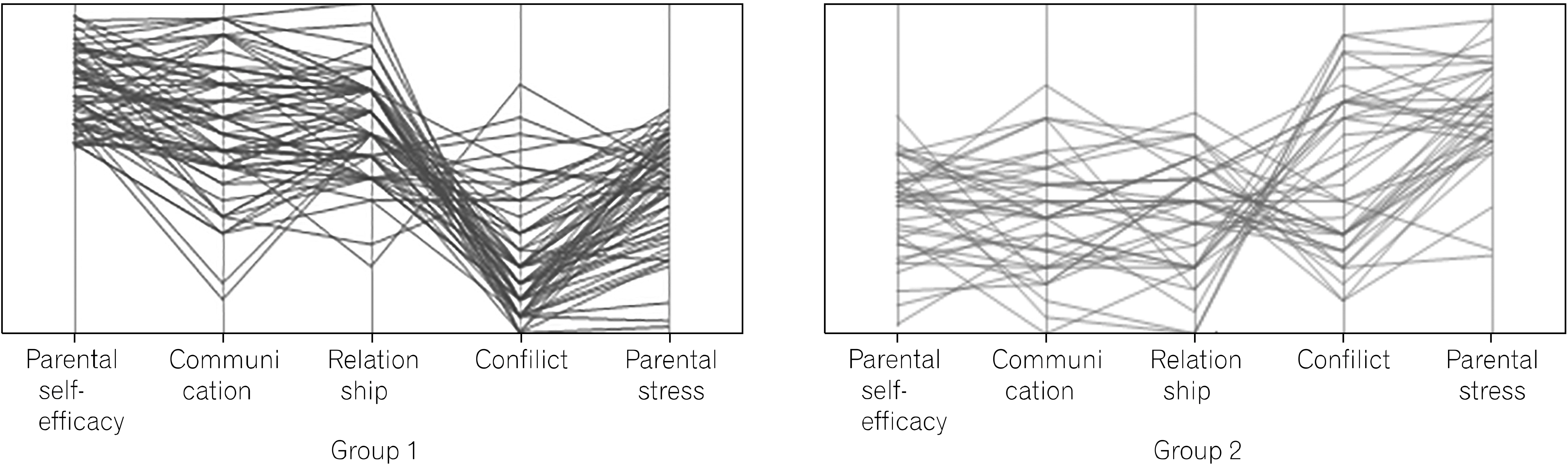

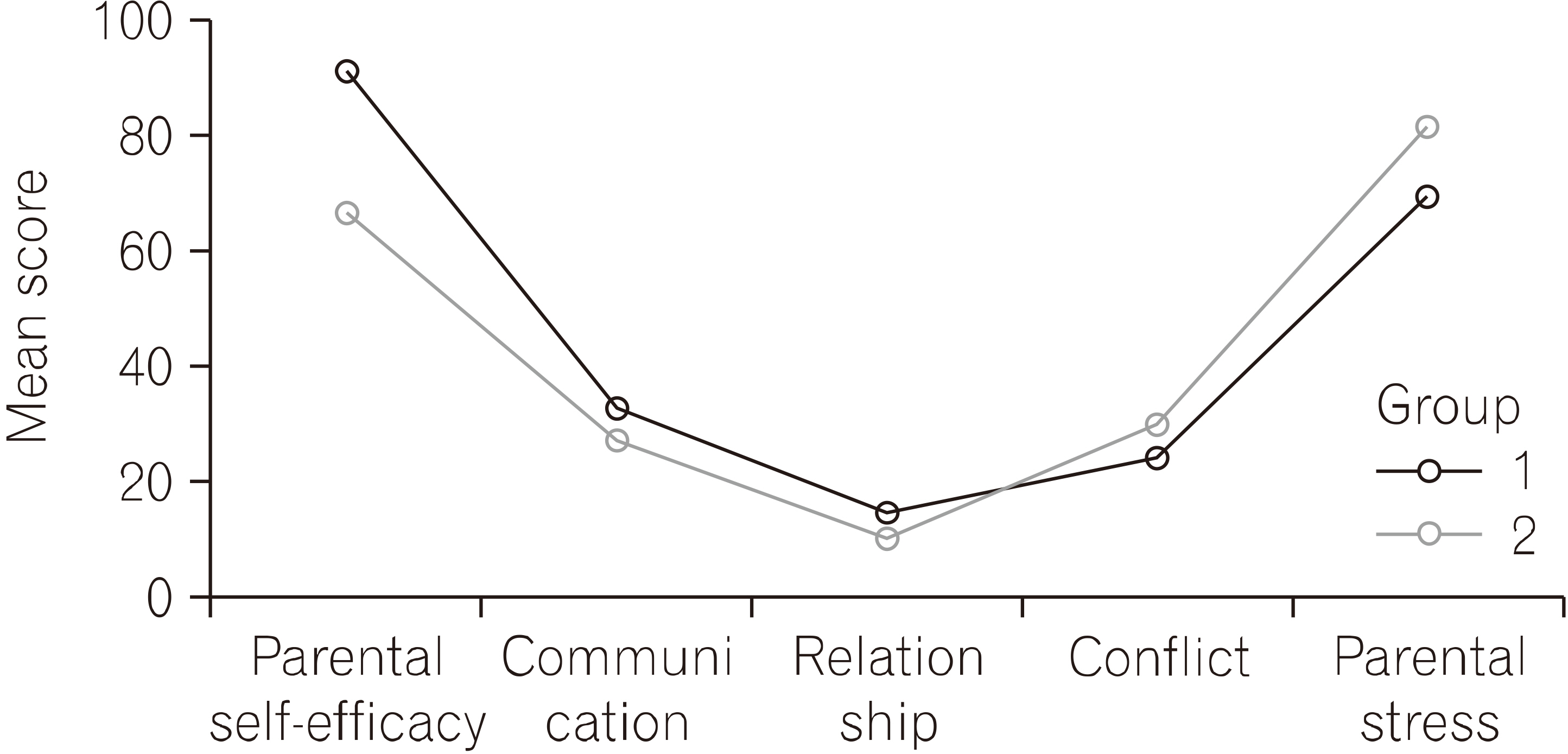

- PCA and hierarchical cluster analysis revealed 2∼3 significant clusters, and in the end, two clusters were chosen. Finally, nonhierarchical cluster analysis by K-means analysis was performed, and the profiles of the two groups are shown in Fig. 1. Group 1 (adequate parent-child relationship) is characterized by relatively higher parental self- efficacy, parent-child communication, and parent- child relationship with low parent-child conflict and parental stress, and 65 participants were classified into this group. Group 2 (inadequate parent-child relationship) is characterized by low parental self-efficacy, parent-child communication, and parent-child relationship with relatively high parent-child conflict and parental stress, and 38 participants were classified into this group (Fig. 2).

- In terms of demographic features, 92 out of 103 parents (89.30%) were mothers, which was sub-stantially higher than the number of fathers (n=11, 10.70%). The mean age was 42.33 years, and the most common household income bracket was moderate (3.01 millionto 6 million won) [n=68, 66.00%]. Eighty-five participants were college gra-duates or higher (82.50%), while 18 (17.50%) were high school graduates. Thirty-nine (37.90%) did not have a religion, and 35 (34.00%) were Christians. Fifty-five (53.40%) were currently employed, and they worked for an average of 32.02±14.95 hours per week. The demographic variable that signi-ficantly differed among clusters was parents’ weekly working hours, where group 2 (38.13 hours) worked for nearly 10 hours more per week compared to group 1 (28.3 hours). The two groups differed significantly in terms of parental self- efficacy, parent-child communication, parentchild relationship, parent-child conflicts, and parental stress. Parental self-efficacy was found to be the key variable for clustering (Table 2).

- 2. Characteristics of parent-child conflicts and parents’ reactions and coping behaviors in each group

- Based on the analysis of qualitative data, sources of parent-child conflicts were classified into five categories. "Learning attitude and grades" describes conflicts occurring as a result of a child’s lack of focus on studying, display of low motivation before tests or school projects, or grades that fallshort of parents’ expectations. This type of conflict was the most common in both groups, occurring in 33.8% of parents in group 1 and 36.8% in group 2. "Life habits" describes conflicts resulting from a child’s failure to maintain punctuality, uphold promises to clean their rooms, and comply with proper etiquette. The frequency of this type of conflict was 29.2% in group 1 and 26.3% in group 2. "Communication and rela-tionships" refers to conflicts resulting from disa-greements and misunderstandings caused by ine-ffective communication between the parent and child. The frequency of this type of conflict was 21.5% in group 1 and 21.0% in group 2. "Cell phones and gaming" refers to conflicts caused by child’s excessive use of cell phones and games, with a frequency of 13.8% in group 1 and 10.5% in group 2. Finally, "child’s problematic behaviors" describe conflicts caused by a child’s habit of stealing, lying, or engaging in other negative behaviors, with a frequency of 3.1% in group 1 and 7.9% in group 2.

- Although both groups generally experienced frustration, anger, worry, discouragement, and disappointment, the two groups differed in their cognitive reactions and responses to the conflict situations. When facing conflict with their child, about 57% of the parents in group 1 tried to understand their children and contemplate ap-propriate reactions. They perceived the conflict to be caused by the child’s problems or strived to consider the child’s stance from various pers-pectives, and they described their expectations for their children. Furthermore, while trying to control their emotions, they carefully thought about how to react to the conflict and provided specific grounds for their behaviors. In terms of responses to their child, these parents tried to explain or reach an agreement with the child in order to resolve the conflict. In contrast, 74% of parents in group 2 immediately reacted by engaging in conflict situations with their children, unlike the parents of group 1. In addition to thinking that their children were disregarding them, these parents blamed themselves for the conflicts and predicted negativeoutcomes for their children’s futures. Moreover, when coping with the conflict, these parents immediately expressed their discontent to their children, and talked in a commanding tone or scolded them, all of which worsened the conflict situation (Table 3).

Results

- In an aim to comprehensively understand parents’ perceptions and responses to parent-child conflicts, we compared and integrated parents’ online self- reported quantitative data regarding parent-child relationships, and parents’ self-described qualitative data for parent-child conflict situations. Cluster analysis based on the five variables related to the parents’ perceived relationshipswith their children (parental self-efficacy, parent-child communication, parent-child relationship, parent-child conflicts, and parental stress) showed that parent-child relationship patterns could be divided into two groups and that the key variable in distinguishing the two groups wasparental self-efficacy. In our study, parental self-efficacy was positively correlated with parent-child communication and parent-child relationship, and negatively correlated with parent child conflict and parental stress. Parental self- efficacy refers to parents’ awareness of their abilities as parents to resolve any problems with their children during the course of rearing and in disciplining them (Johnston et al., 1989). Parental self-efficacy has a significant impact on the quality of parent-child relationships (Park et al., 2009), and is a predictor of not only parent-child communication, but also a child’s academic, social, and emotional adjustment (Shumow et al., 2002). Furthermore, in a process similar to how parental stress affects parenting behaviors, parental self-efficacy also regulates the rejection-restriction parenting behaviors (Park, 2014). Our results, which indicate that parental self-efficacy was the key clustering variable and was strongly correlated with parent-child communication, parentchild relationship, parent-child conflict, and parental stress, are consistent with previous findings, con-firming that improving parental self-efficacy should be a key goal for parent education programs.

- In this study, conflicts related to learning attitude and grades and life habits accounted for more than 60% of all conflicts perceived by parents of adolescents. In a recent qualitative study on Korean mothers with adolescent children, the reason behind mother-child conflicts was mother’s involvement in child’s studies, use of smartphone, mother’s concerns about child’s peer relations, and communication, and the study showed that mothers particularly experience anxiety about their adolescent children’s studies, career, and future (Park, 2016; Kim et al., 2017), which were similar to our findings. Since adolescence is considered the appropriate timeto choose a career path and prepare for it, parents seem to be more interested in their children’s academic performance, and the consequent anxiety induces conflict between them. Moreover, as adolescents mature physically and cognitively, they have an increased desire to be independent from their parents; however, compared to such needs, their actual roles in daily living fall short of parents’ expectations. This causes parents to become disappointed in their children and to realize that the parenting skills used in the past are no longer effective on their children (Kim et al., 2017).

- The two groups in this study were most markedly different in their perception and responses to parent-child conflicts. More than half (57%) of the parents in group 1 focused on the problem itself in a conflict situation and contemplated the most effective way to manage the situation in consi-deration of various factors. They focused on the process of resolving the problem while controlling their own emotions. However, most parents (74%) in group 2 often had cognitive distortions, where they misinterpreted the conflict situation and linked it to an unfavorable future for their children or blamed themselves for causing the conflict. These parents exhibited emotional and immediate reactions. In light of the four types of parental coping strategies suggested by Marceau et al.(2015), namely, problem-focused coping, avoidance coping, regulated emotion-focused coping, and anger/ hostile emotion-focused coping, parents in an adequate parent-child relationship usually employed regulated emotion-focused coping and problem- solving coping. However, most parents in an inadequateparent-child relationship employed anger/ hostile emotion-focused coping. In a parent-child conflict situation, parents’ regulation of their own emotions and focus on problem-solving are helpful strategies that not only positively develop their relationships with their children,but also help them become role models for their children. In contrast, parents’display of negative and hostile emotions toward their children not only hampers problem-solving, but is also emotionally demanding, ultimately aggravating relationships with their children. Therefore, strategies that help parents engage in self-reflection to understand how they perceive the conflict situation and the emotions they experience are necessary for those in inadequate parent-child relationships.

- In addition, although parents in group 2 expressed anger and hostile emotions outwardly, the emotionsembedded in the relationship were mostly shame and self-blame as evidenced by a quote "Is my child embarrassed of me because I look shabby? (Participant 2∼37)". Parental self-blame was found to be associated with parent’s lower state of psychological well-being (Moses, 2010). Parents with feelings of guilt and shame are more likely to experience symptoms of de-pression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress syndrome (PTSS) after negative events (Hawkins et al., 2018). However, parents with high levels of self-com-passion reported fewer symptoms of depression and PTSD (Hawkins et al., 2018) and showed more calm and sympathetic responses to child’s difficult behaviors (Kirby et al., 2017). Thus, it is important to promote parent’s self-compassion which is a potential coping resource for parents.

- An analysis of parents’ perception and responses to the conflicts for both groups provided the following implications for parent education programs that aim to improve parent-child rela-tionships. First, parental self-efficacy should be considered as a key component of parent edu-cation programs that focus on improving parent- child relationships. It should be noted that parental self-efficacy could be improved through various methods, including didactic techniques, modeling, and opportunities to experience success. In particular, the experienceof success in parenting and modeling could be maximized by offering feedback after providing cognitive and com-munication skills training that may be applied in their daily lives. In addition, emotion-focused family therapy, which aimedto develop mastery of emo-tional experience, is an intervention that increases parental efficacy through reducing parents’ mala-daptive self-blame (Strahan et al., 2017) this would be useful in helping parents recognize the emo-tions they experience when they are in conflict with their children.

- Second, parent education programs should provide an opportunity for parents to reflect on their parenting attitudes and beliefs. In conflict situations, parents should be encouraged to ponder their children’s situations and their own responses before immediately and emotionally reacting. Self reflection enables parents to identify their own cognitive errors and distortions, as well as related negative emotions (Laireiter et al., 2003).

- Finally, groups 1 and 2 differ significantly in parents’working hours. The average weekly working hours for group 2 was 38.15 hours, which was about 10 hours longer than that of group 1 (28.30 hours). We can speculate that fatigue and stress caused by long working hours may have contri-buted to parents’ immediate and emotional res-ponses in parent-child conflicts which were made without taking time to ponder the most appro-priate response. Thus, brief and effective parent education programs tailored to working parents are needed.

- The present study demonstrated that it is feasible to apply an online, mixed methods approach to explore parents’ perceptions and responses to parent-child conflicts. This online, mixed methods study is innovative and practical in that both quantitative and qualitative data were collected via study web portals from parents living in diverse areas of Korea. Further studies incor-porating both parents’ and their adolescent children’s perceptions should be conducted. One of the limitations of this study is that we used convenience sampling, so our results cannot be generalized to all parents of adolescents. In addition, fathers’ perceptions and experiences about the relationship with their child have not been reflected enough in this study since fathers comprised only 10.7% of the sample of the present study. In spite of these limitations, this study is meaningful because it contributed to developing effective strategies for parent education by examining parent-child relationships based on integrated quantitative and qualitative data.

- By comparing and integrating qualitative and quantitative data, this study showed that parents’ perceptions and responses to parent-child conflict situations differ depending on the quality of parent-child relationships. The integrated findings identified areas of focus for parent education programs to be tailored to the characteristics of parents and context of parent-child relationship. Our results also suggested that parent education programs should be focused on improving parental self-efficacy. In addition, the programs should provide an opportunity for parents to practice self-reflection and help parents to un-derstand the link between emotion-thought-be-havior based on the cognitive model, thus enabling them to effectively manage parent-child conflict situations. Such programs would promote the healthy development of adolescents by improving the quality of parent-child relationships.

Discussion

-

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

-

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) and grant funded by the Korean government (MEST) (No. 810-20140022).

Notes

| Parental self-efficacy | Communication | Relationship | Conflict | Parental stress | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental self-efficacy | 1.00 | ||||

| Communication | 0.61** | 1.00 | |||

| Relationship | 0.67** | 0.70** | 1.00 | ||

| Conflict | −0.48** | −0.48** | −0.74** | 1.00 | |

| Parental stress | −0.55** | −0.62** | −0.70** | 0.60** | 1.00 |

- 1. Amin NAL, Tam WW, Shorey S. 2018;Enhancing first-time parents' self-efficacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of universal parent education interventions' efficacy. Int J Nurs Stud. :149-162. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.03.021.

- 2. Barnes HL, Olson DH. 1985;Parent-adolescent communication and the circumplex model. Child Development. 56(2):438-447. doi:10.2307/1129732..Article

- 3. Blake RL. 1989;Integrating quantitative and qualitative methods in family research. Fam Syst Med. 7(4):411. doi:10.1037/h0089788..Article

- 4. Bombi , AS , Norcia , AD , Giunta LD, et al. 2015;Parenting practices and child misbehavior: A mixed-method study of Italian mothers and children. Parent Sci Pract. 7:207-228. doi:10.1080/15295192.2015.1053326.Article

- 5. Brook JS, Brook DW, Zhang C, et al. 2009;Pathways from adolescent parent-child conflict to substance use disorders in the fourth decade of life. Am J Addict. 18(3):235-242. doi:10.1080/10550490902786793..ArticlePubMedPMC

- 6. Caprara GV, Regalia C, Scabini E, et al. 2004;Assessment of filial, parental, marital, and collective family efficacy beliefs. Eur J Psychol Assess. 20(4):247-261. doi:10.1027/1015-5759.20.4.247..Article

- 7. Carolina Population Center. 2006 Add health: The national longitudinal study of adolescent health Carolina Population Center. Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth/

- 8. Choi H, Kim M, Park CG, et al. 2012;Parent-child relationships between Korean American adolescents and their parents. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 50(9):20-27. doi:10.3928/02793695-20120807-01..Article

- 9. Choi H, Kim S, Ko H, et al. 2016;Development and preliminary evaluation of culturally specific web‐based intervention for parents of adolescents. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 23(8):489-501. doi:10.1111/jpm.12327..ArticlePubMed

- 10. Creswell JW, Clark VLP. 2017, Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd ed. Sage publications; London.

- 11. Fuligni AJ. In C. Hay (Eds.),2016, Crunching numbers, listening to voices, and looking at the brain to understand family relationships among immigrant families. Methods that matter: Integrating mixed methods for more effective social science research. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: p. 49-63. .Article

- 12. Harris K, Florey F, Tabor J, et al. 2005 Add Health. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design, 2003. [Internet]. Retrieved from https://addhealth.cpc.unc.edu/documentation/study-design/ Article

- 13. Hawkins L, DClinPsy , Luna CM, Holman N, et al. 2018;Parental adjustment following pediatric burn injury: The role of guilt, shame, and self-compassion. J Pediatr Psychol.. 44(2):229-237. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsy079.Article

- 14. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. 2005;Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 15(9):1277-1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687..ArticlePubMed

- 15. Jang HI, Park JH. 2014;The effects of parent-child conflict on behavior problems in early adolescent boys and girls:the moderating role of conflict resolution. Korean J Child Stud. 35(2):171-189. doi:10.5723/KJCS.2014.35.2.171..Article

- 16. Johnston C, Mash EJ. 1989;A measure of parenting satisfaction and efficacy. J Clin Child Psychol. 18(2):167-175. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp1802_8..Article

- 17. Kim AY, Park BK, Kim SJ, et al. 2017;A qualitative study on experiences of parenthood of mothers with adolescents. Korean J Youth Stud. 24(8):161-193. doi:10.21509/KJYS.2017.08.24.8.161..Article

- 18. Kirby JN, Baldwin S. 2018;A randomized micro-trial of loving-kindness mediation to help parents respond to difficult child behavior vignettes. J Child Fam Stud. 24:1614-1628. doi:10.1007/s10826-017-0989-9..

- 19. Klahr AM, McGue M, Iacono WG, et al. 2011;The association between parent-child conflict and adolescent conduct problems over time: Results from a longitudinal adoption study. J Abnorm Psychol. 120(1):46. doi:10.1037/a0021350..ArticlePubMedPMC

- 20. Laireiter AR, Willutzki U. 2003;Self‐reflection and self‐practice in training of cognitive behaviour therapy: an overview. Clin Psychol Psychother. 10(1):19-30. doi:10.1002/cpp.348..Article

- 21. Lee YM, Han JH. 2013;Mothers' perceived experiences of overcoming conflicts between parent and adolescent child caused by parental expectation. Korean J Counseling. 10:1402-1422. doi:10.15703/kjc.14.2.201304.1401.

- 22. Marceau K, Zahn-Waxler C, Shirtcliff EA, et al. 2015;Adolescents', mothers', and fathers' gendered coping strategies during conflict: youth and parent influences on conflict resolution and psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 27(4pt1):1025-1044. doi:10.1017/S0954579415000668..ArticlePubMedPMC

- 23. McLaughlin A, Campbell A, McColgan M. 2016;Adolescent substance use in the context of the family: a qualitative study of young people's views on parent-child attachments, parenting style and parental substance use. Subst Use Misuse. 51(14):1846-1855. doi:10.1080/10826084.2016.1197941..ArticlePubMed

- 24. Morgan Z, Brugha , T , Fryers T, et al. 2012;The effects of parent-child relationships on later life mental health status in two national birth cohorts. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 47(11):1707-1715. doi:10.1007/s00127-012-0481-1..ArticlePubMed

- 25. Moses T. 2010;Exploring parents' self‐blame in relation to adolescents' mental disorders. Fam Relat. 59(2):103-120. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00589.x.Article

- 26. O'Connell ME, Boat T, Warner KE. 2006, Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: progress and possibilities. The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.

- 27. Park HS, Kim YY. 2009;The effects of parenting sense of competence and parent-child communication on parent-child relational satisfaction and parental role satisfaction. J Korean Acad Psych Mental Health Nurs. 18(3):297-304. http://uci.or.kr/G704-001695.2009.18.3.012

- 28. Park JH. 2014;Effect of regulating the parenting efficacy in the relationship between juvenile delinquent's mothers' parenting stresses and parenting behaviors. Forum for Youth Culture. 40(1):93-121. doi:10.17854/ffyc.2014.10.40.93.Article

- 29. Park YS. 2016;Late adolescent-parent conflicts and its relations with parenting behaviors. Korean J School Psychol. 13(2):247-265. doi:10.16983/kjsp.2016.13.2.247..Article

- 30. Quach AS, Epstein NB, Riley PJ, et al. 2015;Effects of parental warmth and academic pressure on anxiety and depression symptoms in Chinese adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 24(1):106-116. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9818-y..Article

- 31. Robin AL, Foster SL. 2002, Negotiating parent-adolescent conflict: a behavioral-family systems approach. Guilford Press; New York.

- 32. Strahan EJ, Stillar A, Files N, et al. 2017;Increasing parental self-efficacy with emotion-focused family therapy for eating disorders: a process model. Person-Centered. 24:doi:10.1080/14779757.2017.1330703..Article

- 33. Shin SH, Ko SJ, Yang YJ, et al. 2014;Comparison of boys' and girls' families for actor and partner effect of stress, depression and parent adolescent communication on middle school students' suicidal ideation: triadic data analysis. J Korean Acad Nurs. 44(3):317-327. doi:10.4040/jkan.2014.44.3.317..ArticlePubMed

- 34. Shumow L, Lomax R. 2002;Parental efficacy: predictor of parenting behavior and adolescent outcomes. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2(2):127-150. doi.10.1207/S15327922PAR0202_03.Article

- 35. Soh SY, Ahn JY, Yang DH, et al. 2014;Parental and adolescent perceptions of transitions during early adolescence: with a focus on the FGI of adolescents and parents. Korea J Youth Counseling. 44:247-279. .

- 36. Sung KM. 2013;Development of a scale to measure stress in parents of adolescents. J Korean Acad Psych Mental Health Nurs. 44: http://uci.or.kr/G704-001695.2013.22.3.006 .Article

- 37. Yuan S, Weiser DA, Fischer JL. 2016;Self-efficacy, parent-child relationships, and academic performance: a comparison of European American and Asian American college students. Soc Psychol Educ. 19(2):261-280. doi:10.1007/s11218-015-9330-x..Article

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

PubReader

PubReader Cite

Cite